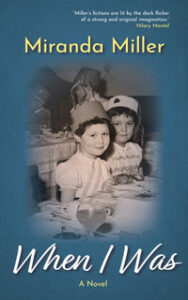

Books

When I Was

A novel of childhood in 1950s London.

Published by Barbican Press, 2025

1953. Viola is three. The young Queen of England is being crowned on a television in the corner of the room. Tubby little Viola gazes out at the party guests in this fancy London house, already alert to human drama.

This is a genteel family in gentle crisis as they have to move from a large house to a tiny flat. Viola’s Anglo-Indian mother hoped for much more from life, while her father gets involved in ghosting the memoir of a chorus girl who married a millionaire. Viola burrows into the adventures of storybooks and battles her three older brothers for attention. A decade passes, and Viola finds friendship and danger among the old and the young. 1950s London with its bomb sites, air raid shelters and attitudes to gender, race, class and sex is vividly present. When I Was provides a delicious, memorable portrait of the writer as a young girl.

Leslie Wilson’s choice is When I Was, by Miranda Miller. What struck me about this novel was the vulnerability of people trying to be adults, and somehow never managing it; the deeply insecure parents are imprisoned by their class and difficult background, trying to negotiate the world without enough tools to do so, at least not enough to fool other adults that they know what they’re doing, and aren’t we all like that at times? The four children are also struggling through their lives, particularly the youngest, an observant, sometimes truculent little girl who loves her parents in spite of their failings. The family relationships ring absolutely true.

There are passages of wonderful comedy, particularly the abortive excursion to Brighton in a hire car, which turns out a disaster, particularly for the car. There’s also deep and devastating sadness. Engaging, perceptive and compassionate, this is a novel that’s hard to put down.

“A lyrically written novel about life in 1950s London, based on the author’s own childhood.”

Miranda Miller has written about topics as diverse as the eighteenth century art and Edwardian London, but she turns to her own life for inspiration in her latest fictional work.

When I Was, Miller’s ninth novel, uses her own childhood as the starting point to invent the life of the Samuell family. At the outset, they live extravagantly, by the mid-point they are all crammed into a small flat, and by the end they are living comfortably, though perhaps not as extravagantly as at the start.

It would be nice to say that the family endures their challenges with a British stiff upper lip, but they do not. Matriarch Colleen mourns for the life she once had. Patriarch Maurice wonders why he can’t get more money from the family trust. The four children have their own challenges: oldest Alex (convinced he’s adopted), twins Will and Ben (to call them rambunctious would be a compliment) and Violet (never satisfied, and based on Miller herself).

The beautifully written book offers a crisp snapshot of life in Great Britain after the war. It opens with the quintessential 1950s British scene– a party with people gathered around the Samuell’s new television watching the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. Other treats are in store, too– an elaborate meal at Veeraswamy’s, Fortnum & Mason delicacies and old-fashioned shopping at Peter Jones and Selfridge’s.

This is a highly recommended novel presenting a slice of life of one family in a bygone era.

Miranda Miller’s ninth novel is her most autobiographical but written not as a memoir but a ‘novel of childhood in 1950s London’.The story starts in 1953 when Viola (or Miranda) is three and just starting to negotiate the complexities of the world around her, with her parents and three older brothers as key characters. The third-person narrative perspective sometimes takes Viola’s childish view of the world but also often shifts to the adults’ perspectives, allowing the reader to understand the bigger picture and the issues at stake. We are given, therefore, scenes that Viola would not have witnessed directly, although it helps us comprehend why the adults behave the way they do. In some ways, I would have enjoyed the novel more had it consistently taken Viola’s perspective and given us a limited viewpoint raising more questions and ambiguities (shades of Henry James’ What Maisie Knew).

And the issues are that Viola’s genteel upbringing is about to be threatened by a family financial crisis, which results in a move to a smaller flat and more constrained circumstances. In addition, Viola’s father is writing a memoir about a chorus girl who married a millionaire, and his long research visits to her home are putting increasing strains on his marriage.

The novel is an easy read and gives an insight into London life in the 1950s. The touch is light and often humorous. Class is a key concern, indicative of the time and shown in the contrasting lives of the family and their servants. The very brief portraits of the servants emphasise these differences. My main criticism is that, while the characterisation is interesting, I did not find it particularly sympathetic. However, overall, there is much to recommend this novel, particularly readers interested in the social changes happening in post-war British society.

Miranda is a gifted novelist who takes you inside the heads of each member of a North London family in the early 1950s. Seen through the eyes of 4-year old Viola — based on Miranda herself – it tells the story of how, due to the fecklessness of her father, the family is forced to move from a large and comfortable house, to a tiny squalid flat in post-war London, while her unhappy mother cannot reconcile herself to these events. It pulls you in and does not let you go.

The novel is very much present for me: the incredible vividness of the racial issues, the relation of the twins, and above all the darling Viola – her innocence and observations. One can see the writer in the making. How shocking that abuse was, how believable. You treated the parents with admirable honesty and kindness really, eliciting the complexity of their pasts and characters.